Bringing Gabon’s Rivers Into the 21st Century

First river flow measurements in 40 years help Gabon maintain healthy river systems

With its apparently unbroken forest cover, six-and-a-half feet of annual rainfall, and mighty rivers draining into the Atlantic, Gabon seems like a place where nature’s cycles continue as they have since pre-human times.

But in fact, huge change is underway under that forest canopy and along those rivers. The central African country’s government plans to harness more of nature’s power to drive its economy and improve the lives of its two million residents.

Gabon's energy master plans identify more than 30 new hydropower plants that could be built in the next decade, alongside capacity upgrades of the four already there that today provide 40 percent of Gabon’s electricity. The aim is to increase hydropower electricity generation from 700 megawatts to at least 1,200 megawatts.

The Problem With Old Data

There is a problem, though. Generating the optimum amount of electricity from the most efficient power plants requires a comprehensive understanding of how much water flows through the rivers that feed those plants.

But the data Gabon relies on for that is about 40 years old, the bulk of which was last collected from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. With a changing landscape and a changing climate, that data no longer reflects reality.

Some timber logging is degrading forests, and plantation farming — mostly for palm oil — is increasing. Infrastructure is expanding, and industry is growing fast. Rainfall is increasingly erratic, and the combination of poor land use and management in areas of heavy rainfall increases erosion, augmenting sediment run-off into rivers and reservoirs.

Now The Nature Conservancy, along with the French Research Institute for Development (IRD), is helping to gather fresh information about the volume, speed, and flow of Gabon’s rivers, working alongside Gabon’s Ministry of Energy, the Gabon Research Institute, and its National Parks Agency.

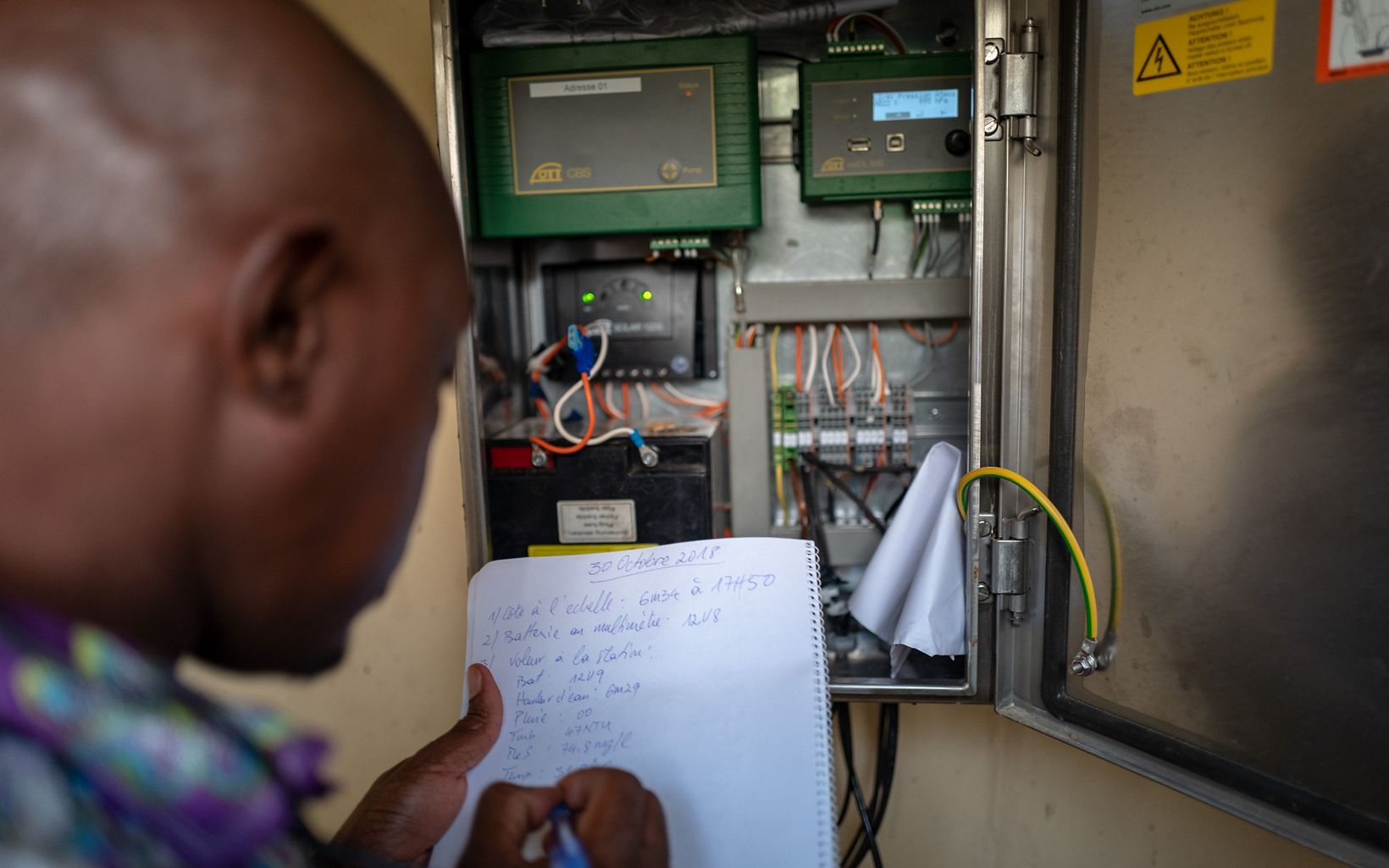

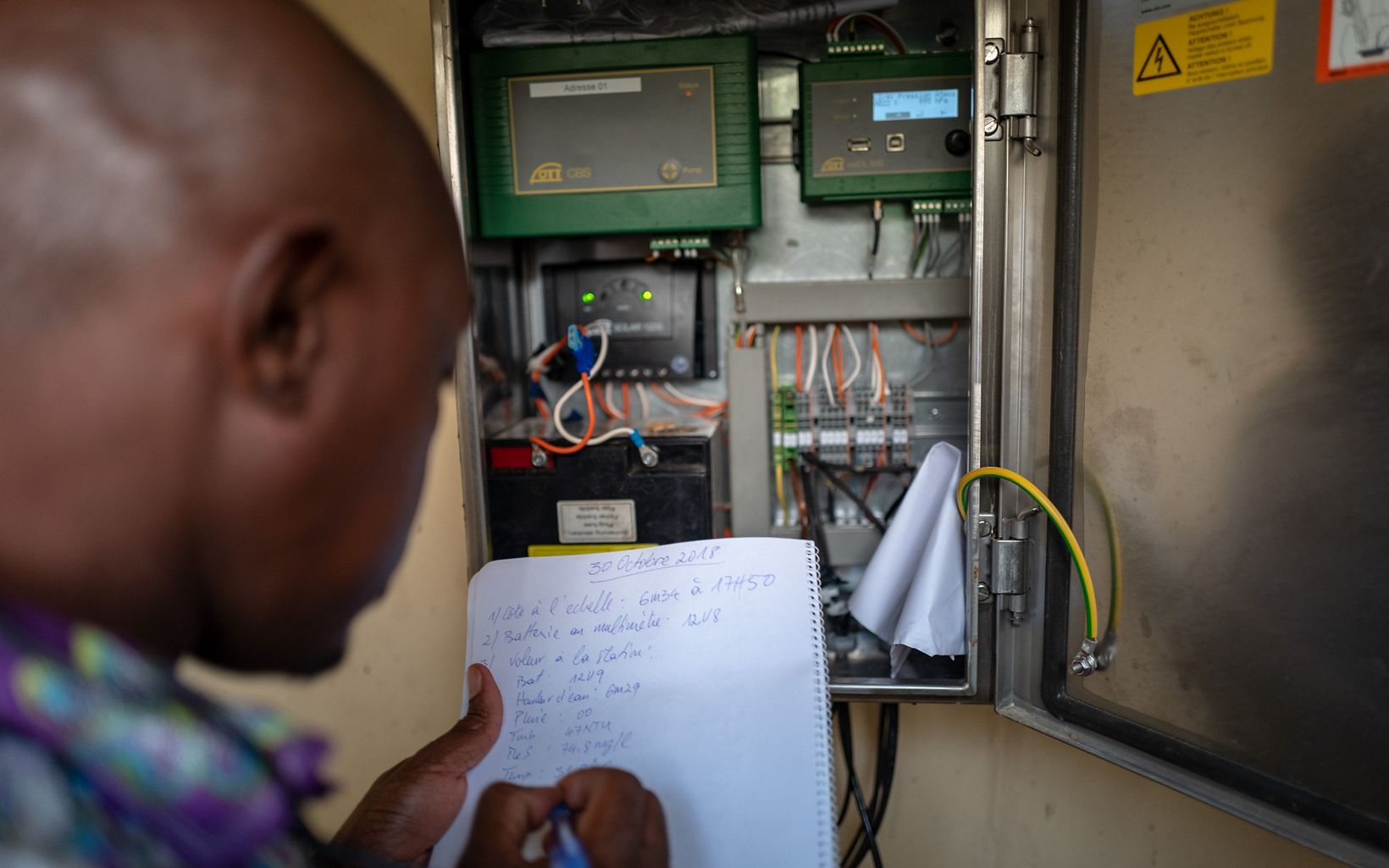

In late 2017, TNC and partner scientists installed two pilot stations with monitoring equipment along two major rivers, the Ogooué and the Mbé.

Smart new gauges plot each river’s rise and fall, the speed and flow of their waters, their turbidity, and how much sediment they carry. On the Ogooué, weather data including rainfall, wind direction, and solar intensity are also captured.

Some of the data is pinged in real time via SIM cards connected to cell phone networks directly to data hubs in the city. The rest is downloaded manually once a month.

“Gabon has an impressive plan to expand its hydropower generation, and is going into that process with the intention to develop that infrastructure in the most ecologically sensitive way it can,” says Marie-Claire Paiz, The Nature Conservancy’s Gabon Program Director.

“A key missing element was an up-to-date understanding of the real available supply of water in the rivers for these new dams. Understanding river flows is essential to optimize energy production, but also to better protect and manage freshwater biodiversity. It’s very important both for the country’s economy and its environment that its plans and decisions can be made according to the situation as it is now, not how it was 40 years ago.”

For the data collected by the gauge stations to remain accurate and relevant over time, it's essential to have a rating curve. The team is currently working on creating one for each river using an ADCP (Acoustic Doppler Current Profiles) device called a RiverRay. An ADCP is similar to a sonar and uses sound waves to measure both the depth of the river and the velocity of the water at any given time and point. To build a rating curve, river depth and velocity need to be measured several times throughout a full year cycle, and the measured data plotted on a graph. The resulting rating curve is used as a calibration baseline for the data collected automatically by the permanent gauge stations.

A Powerful Future for Gabon

The Mbé watershed feeds the two main dams, Tchimbélé and Kinguélé, that together provide half the electricity needed by the capital, Libreville, where half of Gabon’s population lives.

That demand is increasing by at least seven to 10 percent every year, driven by the growing urban population and industrialization, including wood processing and mineral smelters.

Already, there are regular power cuts driven by a murky understanding of how much sediment lies in the dams’ reservoirs, and when water flows might slow. Polluting and expensive thermal energy ends up plugging the power gap, but as many of those diesel-burning plants are expected to close in the next two years, more blackouts are expected.

That means the new data from the station upstream from those reservoirs on the Mbé will immediately be used to help energy authorities optimize hydropower from their existing plants. A new hydropower plant is currently under study further down on that river and on the neighboring river, and all the feasibility assessments rely on old data, which is a hinderance for planning for optimum design and operations.

Information from the other station on the Ogooué can also help direct plans for new infrastructure.

Based on the experience gathered with these two pilot stations, TNC helped direct new funding for the government to install 10 more gauge stations by late 2019, and will be providing ongoing support to the local partners who will keep the stations running for years to come.

The benefits are more than economic, however. River flows' seasonal cycles represent an essential ecological feature of freshwater ecosystems, triggering key steps in the life cycle of many aquatic species. By understanding how river flows vary throughout the year, new infrastructure can be designed to maintain natural flow patterns and volumes that are the hallmark of healthy rivers and associated biodiversity.

Installing the river gauge stations stands alongside other work The Nature Conservancy is doing in Gabon to provide the authorities with the sound science they need to sustainably develop their natural resources.

“Gabon really has the understanding already that their healthy ecosystems are precious and, far from being sacrificed in the rush to develop, they are in fact integral to that development,” Marie-Claire says.

Gauge Station Data Collection